Jan 14 2014

And around and around it goes | Bill Waddell

See on Scoop.it – lean manufacturing

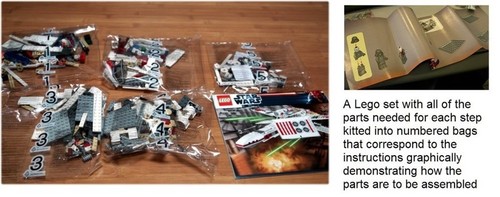

You can do many things with Legos, like our own Leanix™games, and this article shows an example where a team of accountants who were given parts in kits and assembly instructions from Lego performed 40% faster than a team of engineers who were given the parts in single-item bags and only pictures of the finished assemblies.

In drawing far-reaching conclusions from this example, however, Bill is comparing apples and oranges. It was faster to assemble from kits because somebody at Lego had kitted the parts, and the kits were complete and accurate. A fair comparison would require including the time needed for this. Kitting may still win, but not by a 40% landslide.

In a real manufacturing situation, you buy components and materials from specialized suppliers and, if you want kits, you have to put them together before assembly. Whether it is justified or not depends on what you are producing and on the parts you use.

Let us assume you are making custom-configured products on a mixed-flow line, but there is one screw that is used in all configurations. You are better off presenting this screw on the line side in bins than distributing it across kits.

On the other hand, it often makes sense to kit configuration-specific parts off line. It requires less labor overall but, most importantly, the work of kitting is done in parallel with assembly rather than in the final assembly sequence, which can cut in half the start-to-finish assembly time on the line.

Even then, however, you have issues with kitting errors by operators who don’t know the product, kits rendered unusable by a single defective part, and part stealing from kits, which is often done as an immediate remedy to the above.

See on www.idatix.com

Jan 15 2014

The “Making Things in Japan Tour” — April 20-26, 2014

You may have noticed a new widget on our sidebar, which links to a site about this tour and registration through Eventbrite. Brad Schmidt and I are organizing this together, and I am thrilled to be working with him again.

Why go to Japan to visit plants in 2014? Until the 1970s, Japanese manufacturing got no respect. When I headed there as an engineering graduate in 1977, a classmate of mine called this move “career suicide.” Whatever competitive success Japanese companies had achieved by then was chalked up to long hours and low wages, much the way China is perceived today.

Then came the 1980s and the discovery that there was more to it — that should be looked into and studied — coupled with fear that “Japan, Inc.” was going to take over the world. The two-decade recession that hit Japan in the early 1990s put a quick end to the paranoia and, more slowly, dampened the enthusiasm for so-called “Japanese methods” in manufacturing and management.

The renewed neglect of Japan today, however, is no more rational than was the exuberance of the 1980s. Japan today has a highly trained but aging and expensive work force, and is facing the same challenges as other advanced economies. And it still has the most advanced, most productive, manufacturing plants in the world, with the best quality. It is still the go-to place for manufacturing excellence, where the art of making things (Monozukuri, 物作り) is valued and honored both in companies and in society at large.

For those who don’t know him, Brad Schmidt is a South African raised in Japan, a graduate of Japanese schools, and perfectly bilingual. With 128 tours in 15 years under his belt and counting, he is a pro. Few people have seen the inside of more Japanese factories than him, and he has the logistics of tours worked out, from airport pickups to interpreters, transportation and lodging. That leaves me with the easy part: promoting this tour in tour in the US and then going on it to help answer participants’ questions and facilitate site reviews.

Share this:

Like this:

By Michel Baudin • Announcements 0 • Tags: Japan tour, Lean