Oct 10 2012

7 Charts About America’s Manufacturing Industry

See on Scoop.it – lean manufacturing

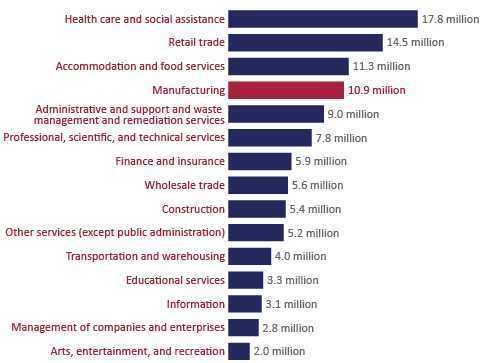

Seven Charts from the US Census Bureau That Show How Essential Manufacturing Remains To America. These charts do not include other useful numbers from the US Census Bureau, such as value-added per industry, with value-added defined as Sales – External Inputs, where the external inputs are comprised of materials, energy, and outsourced services.

See on www.businessinsider.com

Oct 11 2012

To journalists: if you write about Lean, check your facts!

An otherwise informative newspaper story about a company’s Lean approach in a local newspaper contains the following paragraph:

This is a remarkable paragraph. Other than saying that Kaizen is Japanese, every statement in it is inaccurate. Let us review them one by one:

The rest of the article is actually interesting, informative, and credible about the specifics of the case. It didn’t need a paragraph of background. If, as a journalist, you write about a case of Lean implementation, don’t write such a paragraph without checking the facts.

Share this:

Like this:

By Michel Baudin • Press clippings 2 • Tags: Deming, Kaizen, Lean