Nov 21 2012

Mitigating “Mura,” or unevenness

The Japanese word Mura (ムラor斑) is the third member of the Muri, Muda, Mura axis of manufacturing evils. It means unevenness. In terms of volume of activity, if Muri refers to overburdening resources, Mura then really is the conjunction of overburdening some resources while others wait, or of alternating over time between overburdening and underutilizing the same resources.

Unevenness, however, is not only about volumes, but about quality as well. Unevenness in products is even synonymous with bad quality. From production managers facing “unpredictable” environments to academics promoting genetic algorithms or other cures, everyone bemoans how variable, or uneven, manufacturing is. The litany of causes is endless. Following are a few points that I think may clarify the issues:

- Mura in space, Mura in time, and Mura in space and time

- Degrees of severity: Deterministic, random, and uncertain environments

- What is special about Manufacturing?

- Internal versus external causes of unevenness

- Most useful skills in dealing with Mura

Mura in space, Mura in time, and Mura in space and time

Mura in space is imbalance in the work loads or utilization among resources at the same time; Mura in time, variability in the work load of a resource over time. The two can be present in the same factory. You may notice a kitting team working feverishly while the next one is waiting but, two hours later, you find the roles reversed.

Mura is often symbolized by two trucks arriving in sequence with different loads. I tend to think of working with Mura as moving around a city built on hills. A city built on a plain is even and easy to cross, and is often planned with a grid of numbered streets, like Manhattan in New York, or Kyoto. A city built on hills is uneven and offers many obstacles. San Francisco is built on hills, but its planners have chosen to ignore the terrain and slap on it a grid of straight streets. It makes for great views and dramatic car chases, but its steep slopes challenge your engine, your suspension, and your parking skills. Most hilly cities, like Nagasaki, Japan, for example, instead have streets that follow contour lines and therefore meander. The path by car from point A to point B may be longer than a straight line, but it is a smooth ride.

Navigating the peaks and valleys of product demand is like driving in a hilly city. If you just go straight, you keep alternating between pressing the accelerator and the brake, but by hugging contour lines, you can reach to your destination while going at a steady pace. This is what fighting Mura is about.

Degrees of severity: Deterministic, random, and uncertain environments

Some businesses are deterministic. They are “boring” and predictable. They have no variability. A manager once explained to me the electricity meter business in the market his plant was serving, as follows: “There are 20 million households with electricity meters in the country. Each meter lasts 20 years. Every year, I have to make 1 million.” The same products are made for many years, in stable quantities, and with mature processes that have no problem meeting tolerances. Of course, it only lasts until the advent of a disruptive technology, like smart meters.

This kind of environment is not common but it does exist. If your are in one, you should focus your improvement efforts on the opportunities it offers, and avoid tools that are overkill for it. For example, large, diversified companies that make a corporate decision to deploy the same planning and scheduling system in all their plants burden their simplest and most stable business units with unnecessary complexity.

Other business have variations that can be best be described as fluctuations around a smooth trend. If you make consumer goods, the demand every day is the result of decisions from a large number independent agents and will vary in both aggregate volume and mix, but within ranges that can be predicted. In terms of quality characteristics, if you fire ceramics, they shrink, by factors that still vary, even though we have been using this process for thousands of years. This level of variability is very common. The best term to describe it is randomness, and there is a rich body of knowledge on ways to work with it, including the Kanban system to regulate fluctuating flows and techniques to adjust processes in order to obtain consistent results from materials that are not. In ceramics, for example, you make your parts from a slurry that is a moving average of batches of powders received from the supplier, in order to even out their characteristics.

Contrast this with a toy manufacturer who cannot tell ahead of time which one or two products will be hits at Christmas, when most of the year’s sales occur. In process technology, there are similar differences in variability between mature, stable industries and high technology suffering from events like “yield crashes” during which a manufacturing organization “loses the recipe” for a product. Various terms are used to describe such situations, which, following Matheron, I call uncertainty. In such circumstances, the best you can expect from the techniques used to deal with randomness is to let you know that they no longer work. For example, dealerships can shield your plants from fluctuations in consumer purchases, where direct selling would let you find out sooner when demand drops for good or when consumer tastes change.

Calling our environment deterministic, random, or uncertain is always a judgment call. The deterministic electricity meter business turns uncertain with the advent of smart meters. If you view your environment as random, you expect fluctuations with a predictable range, and the signal of a shift into uncertainty manifests itself in changes beyond this range. You can use a variety of tests to detect that such as shift has occurred. Furthermore, with the possible exception of quantum physics, randomness is always in the eye of the beholder, and not intrinsic to a phenomenon.

What is special about Manufacturing?

Manufacturing is not the only kind of business to have high overhead; others include aviation or hospitals. In all such cases, companies must invest upfront in resources that pay off over time, and this is easiest to achieve with activities that place a balanced load on all resources and don’t vary over time — that is, without Mura.

Internal versus external causes of unevenness

Some unevenness comes from outside the organization, in many forms:

- Fickle customers.

- Seasonal variations in demand as in the toy industry.

- Seasonal variations in supply, such as crop seasons in the food industry.

- Changes in the macro-economy, such as a financial crisis.

- Natural disasters, like earthquakes, tsunamis, and floods.

- Raw materials with uneven characteristics, like ores or electronic waste for recycling.

- Epidemics, as when 10% of your work force has the flu.

- Unreliable suppliers.

- …

You do not have the power to eliminate this kind of unevenness, but you can use countermeasures to mitigate its effects. On the other hand, you can and should eliminate unevenness that is self-inflicted. If you have not paid attention to balancing the work load of the various stations on your production lines, you are likely to have both overburdened and underutilized operators. Because of the different roles machines play, the workload can rarely be balanced across machines in a line, but the workloads of operators can be.

If you order materials from suppliers, for example by relying on an ERP system to issue orders by an algorithm for timing and quantities that you don’t undertand, you may well cause alternations of feast and famine in your suppliers’ order books for materials that you, in fact, consume at a steady pace. This creates unevenness not only in your suppliers’ operations, but also in your internal logistics. In The Lean Turnaround, Art Byrne explains that, at Wiremold, he eliminated volume discounts and incentives for Sales to book the largest possible orders. Instead, he preferred a steady flow of small orders, that smoothed the aggregate demand.

Not all resources need to be treated the same way. You want resources that can be described as producers to be generating useful output all the time. Other resources, which we may call responders, must be available when needed, and this is a radically different objective. Unevenness is an enemy for producers, but, unless responders’ work loads provide enough slack, they are unable to respond. Firefighters fighting fires 100% of the time would be unavailable when a new fire breaks out, and the same logic applies to maintenance technicians and operators who work as floaters on a production line. And it applies to machines as well as people. In a machine shop, for example, machines that carry out the primary processes, like hobbing a gear or milling pockets in a slab, are producers, while devices used for secondary processes, like deburring or cleaning, are responders. This is often, but not always, related to the cost of the machines, with expensive machines as producers and cheap ones as responders. However, some of the most expensive equipment, like machining centers, may be bought for its flexibility more than for its capacity, in which case its primary role is to respond to orders for short runs or prototypes.

Most useful skills in dealing with Mura

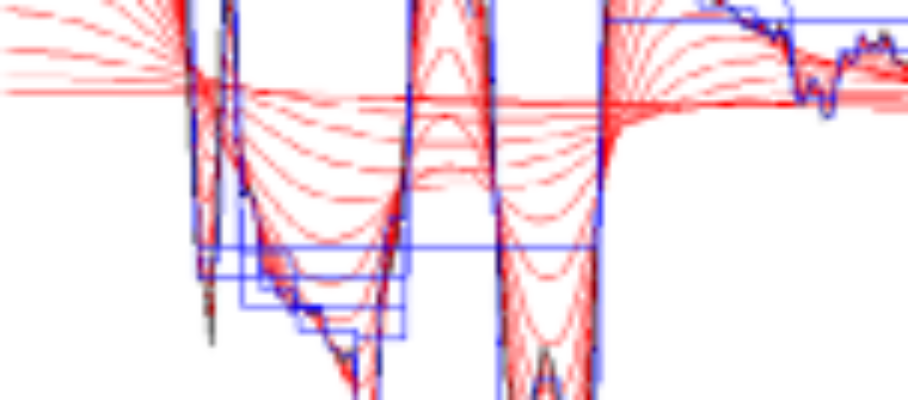

Permanently uneven workloads among operators can be addressed by balancing, using Yamazumi charts for manual operations and work-combination charts for operations involving people and machines. If the unevenness pattern shifts or oscillates over time, then the workload itself needs to be smoothed, with is done by the various techniques known as heijunka.

Many organizations are not aware of Mura as a problem, and, when aware, are oblivious to patterns in the unevenness that can be used to mitigate or eliminate it. Management, for example, may be struggling to cope with occasional large orders and fail to notice that they arrive like clockwork every other Wednesday from the same customer. A modicum of data mining skills is needed to recognize such patterns in the records of plant activity.

Nov 22 2012

Finding local roots for Lean – Everywhere

Lean is from Japan, and even more specifically from one Japanese company. Outside of Japan, however, the foreign origin of the concepts impedes their acceptance. In every country where I’ve been active, I have found the ability to link Lean to local founders a critical advantage. The people whose support you need would like to think that Lean was essentially “invented here,” and that foreigners at best added minor details. Identifying local ancestors in a country’s intellectual tradition takes some research, and then you may need to err on the side of giving more credit than is due.

In the US, using the word “Lean” rather than TPS is already a means of making it less foreign, and it is not difficult to paint Lean as a continuation of US developments from the 19th and 20th century, ranging from interchangeable parts technology to TWI. Ford’s system is a direct ancestor to Lean, as acknowledged by Toyota. On this basis, the American literature on Lean has gradually been drifting towards attributing Lean to Henry Ford. Fact checkers disagree, but it makes many Americans feel better.

Elsewhere, it is not as obvious to find a filiation. Following are a few examples of what I found:

Britain, as the Olympic opening ceremonies reminded us, was home to the industrial revolution. In terms of worldwide share of market for manufactured goods, however, Britain peaked about 1870, and the thinkers that come to mind about British manufacturing are economists like Adam Smith or David Ricardo, whose theories were based on observations of early manufacturing practices, but whose contributions were not on the specifics of plant design or operations. They are too remote to be linked in any way to Lean.

For France, I have asked everybody I know there for nominations but have yet to receive any. The French have invented many products and processes, but I have not been able to identify French pioneers in production systems who could provide a link to Lean. And there are many other countries where the search may be fruitless.

Even though people in China and India have been making things for thousands of years,I don’t know any names of local forerunners of Lean in these countries. China has only emerged as a world-class manufacturing power in the last few decades and I have, unfortunately, never been to India. There are many other countries on which I don’t have this kind of information, and nominations are welcome.

Share this:

Like this:

By Michel Baudin • Management 6 • Tags: Ford, Gastev, Henry Ford, industrial engineering, Lean, Lean implementation, TWI