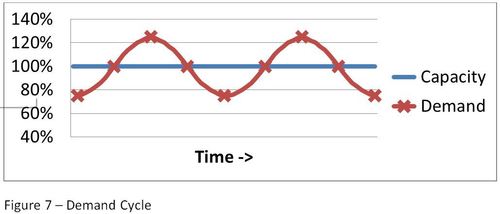

John Dyer presents the capacity of a business as a constraint set by the slowest operation in its process, also known as its bottleneck. In manufacturing, at least, it is more realistics to think of it as fuzzy.

If a solid line exists, we don’t usually know exactly where it is. Even an operations manager who claims to know it won’t share that information with colleagues. Right after claiming in a meeting that production is running full blast, he or she miraculously finds a way to squeeze 15% more out of it.

If a perceived bottleneck is a purely human process requiring no unusual skills, it can eliminated by rebalancing the work. Dyer’s discussion is centered on where it is a machine and its capacity can be increased by process improvement.

But does this mean that continuous improvement should be focused exclusively on the bottleneck? In many cases, the bottleneck is the most sophisticated machine on the floor, and increasing its capacity requires engineering knowledge that is not present in the factory’s work force, and can only be done by bringing in outside experts.

On the other hand, the work force has the skills needed to improve the performance of other operations. This can ensure that the bottleneck has the materials it needs at all times, and free human resources that can be trained to operate and maintain the bottleneck, and eventually to improve it.

This article has a “Part 2” about why it is so difficult to work with in-house suppliers . Dyer’s term for in-house suppliers is “intercompany suppliers,” which confused me, because I took “intercompany” to mean “between companies,” the way “international” means “between countries.”

His point is that in-house customers may be bad for a supplier because transfer prices calculated on a cost-plus basis can be below market prices. This causes in-house suppliers to give preferential treatment to their external customers.

A remedy that Dyer does not seem to consider is to make transfer prices between divisions match market prices. This works as long as the supplier division has external customers — or the customer division external suppliers — through which market prices can be known.

In many cases, in-house suppliers make parts based on the company’s unique technology, that have no outside market, and for which there is no market price. Transfer prices then have to be negotiated in a way that is “fair” to both sides. Figuring out what that means is a conflictual process, that is avoided by treating the supplying division as a cost center rather than a profit-and-loss center.

Nov 8 2013

Demand/Capacity Curve | John Dyer | IndustryWeek

See on Scoop.it – lean manufacturing

“True company growth can be achieved when the maximum capacity is increased by breaking bottlenecks and the sales team makes promises to the customers that the business process can support.”

John Dyer presents the capacity of a business as a constraint set by the slowest operation in its process, also known as its bottleneck. In manufacturing, at least, it is more realistics to think of it as fuzzy.

If a solid line exists, we don’t usually know exactly where it is. Even an operations manager who claims to know it won’t share that information with colleagues. Right after claiming in a meeting that production is running full blast, he or she miraculously finds a way to squeeze 15% more out of it.

If a perceived bottleneck is a purely human process requiring no unusual skills, it can eliminated by rebalancing the work. Dyer’s discussion is centered on where it is a machine and its capacity can be increased by process improvement.

But does this mean that continuous improvement should be focused exclusively on the bottleneck? In many cases, the bottleneck is the most sophisticated machine on the floor, and increasing its capacity requires engineering knowledge that is not present in the factory’s work force, and can only be done by bringing in outside experts.

On the other hand, the work force has the skills needed to improve the performance of other operations. This can ensure that the bottleneck has the materials it needs at all times, and free human resources that can be trained to operate and maintain the bottleneck, and eventually to improve it.

This article has a “Part 2” about why it is so difficult to work with in-house suppliers . Dyer’s term for in-house suppliers is “intercompany suppliers,” which confused me, because I took “intercompany” to mean “between companies,” the way “international” means “between countries.”

His point is that in-house customers may be bad for a supplier because transfer prices calculated on a cost-plus basis can be below market prices. This causes in-house suppliers to give preferential treatment to their external customers.

A remedy that Dyer does not seem to consider is to make transfer prices between divisions match market prices. This works as long as the supplier division has external customers — or the customer division external suppliers — through which market prices can be known.

In many cases, in-house suppliers make parts based on the company’s unique technology, that have no outside market, and for which there is no market price. Transfer prices then have to be negotiated in a way that is “fair” to both sides. Figuring out what that means is a conflictual process, that is avoided by treating the supplying division as a cost center rather than a profit-and-loss center.

See on www.industryweek.com

Contents

Share this:

Like this:

Related

By Michel Baudin • Press clippings 0 • Tags: bottleneck, capacity, Continuous improvement, Supply chain