Feb 27 2020

Toyota Precepts and Public Relations

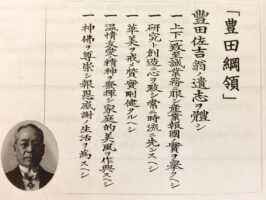

Sam MacPherson started a discussion on LinkedIn about Toyota founder Sakichi Toyoda’s 5 Precepts. Sakichi Toyoda died in 1930 and, 5 years later, Kiichiro and Risaburo Toyoda pulled together 5 precepts that he had lived to share with Toyota employees. Sam thinks that these 5 precepts are the key to understanding culture, global business practices, and company Hoshins.

Contents

The English version

On LinkedIn, Sam posted a copy of the 1935 original document and the English “translation” available on Toyota’s website:

- Always be faithful to your duties, thereby contributing to the company and greater good.

- Always be studious and creative, stay ahead of the times.

- Always be practical and avoid frivolity.

- Always strive to build a homelike atmosphere at work is warm and friendly.

- Always have respect for God and remember to be grateful at all times.

Even as stated in the official translation, Point 5 is unacceptable. An employer has no business mandating religion to employees. Points 1 to 4 are generic about working hard to make the world a better place, stay current in your knowledge, be thrifty and play well with others. This kind of homilies is a common product of corporate public relations.

There is no exact 1-to-1 matching in the lists of other companies but they tend to have 5 entries. The lists cover the same ground, at such a level of abstraction that it is nearly impossible to prove that the company is violating its own principles.

Mary Barra’s principles at GM

By comparison, here is a list of principles from GM CEO Mary Barra:

- Quiet leadership is a workable model for a senior executive.

- Bring order into a chaotic world.

- Build your own expanding hedgehog — meaning what you are passionate about and good at that will reward you economically.

- Never stop learning.

- Treat people with dignity and respect.

The Principles of the HP Way

Or the 5 principles of the HP Way, as formulated by David Packard in 1992:

- We have trust and respect for individuals

- We focus on a high level of achievement and contribution

- We conduct our business with uncompromising integrity

- We achieve our common objectives through teamwork

- We encourage flexibility and innovation

The Japanese Version

Sam’s post sent me scrambling to figure out what the Toyodas had actually written and how close it is to the official English version. It was particularly challenging because it’s not modern Japanese.

Alternative Translation

So here is the fruit of my efforts:

- You must bear the fruits of industry to reward the country by subordinating yourself and working faithfully.

- You must stay ahead of the times by putting your heart into research and creation.

- You must be simple and strong by avoiding excess.

- You must cultivate a beautiful, home-like atmosphere by showing a spirit of passionate friendship.

- You must respect Shintoism and Buddhism and live a life of gratitude.

Points 2,3, and 4 are roughly similar to the official English version, just more forcefully stated.

Point 1 is particularly difficult and seems to have been crafted to placate the nationalist government of the 1930s. See below.

The original Point 5 is even worse than the English version by being specific about Shintoism and Buddhism. In today’s Japan, most of the population is counted as being both Shintoist and Buddhist. In reality, you rarely meet a believer.

The Challenges of Point 1

Making sense of a 1935 document is a challenge and not just because the Japanese language has evolved but also because the government at the time had a nationalist ideology that business people had to humor.

I started from the print version on the Toyota website. It comes out as

上下一致、至誠業務に服し、産業報国の実を拳ぐべし

It matches Sam’s picture, except for modernized spelling.

Working with Google Translate

Google translate then turned it into the following fragment of dadaist poetry:

“Serve in unanimous and sincere business, and fist on the fruits of the Industrial News Country”

Google Translate was smart enough, however, to suggest that 拳ぐ (fist) was an error and should have been 挙ぐ (raise) instead. The characters are almost the same. The alternative has one less stroke and a different meaning. With that change, Google Translate made it:

“Serve in unanimous and sincere business, and bear the fruit of the Industrial News Country”

My 1960s vintage Japanese dictionary then confirmed that the character in the original picture, 擧, is indeed an old version of 挙, misspelled on the Toyota website.

Help from Friends

“Industrial News Country” (産業報国), however, remained a mystery. This word or phrase is not in any Japanese dictionary I have, including Japan’s equivalent of Webster’s or the OED, the Kojien (広辞苑).

Jon Miller cleared this up. It’s short for 産業を通して国に報いる, meaning “give back to the country though industrial development”. It makes it clear that Point 1 was not about the greater good but about strengthening Japan in the run-up to World War II.

“The precepts were heavily influenced by the context of Japanese society at the time. The social background was that you were supposed to improve industry as a family, as children of the emperor, and return goodwill to the emperor for his good graces.

The original idea is not acceptable in a modern company and even less in a multinational. This is why they tried to dilute it in the translation.”

Car Makers Are Not Philosophers

The bottom line is that Sakichi Toyoda was a great inventor of looms. Kiichiro and Risaburo Toyoda cannot be blamed for posting precepts based on the ideology of the authoritarian government of the time. They may well have perceived it as mandatory to stay in business but it’s PR, not philosophy.

Sam pointed out that inventors could be philosophers, and used Henry Ford as an example, with Today and Tomorrow as his book of philosophy. It’s true that you can have a day job and be a philosopher. Marcus Aurelius was emperor of Rome and Spinoza cut eyeglasses. Philosophers, however, don’t use ghostwriters. Henry Ford did. Philosophy is the most difficult intellectual endeavor of all, and the job of philosopher of manufacturing has yet to be filled.

Modernizing the precepts for the multinational company that Toyota has become is understandable as well. What is questionable is acting as if the modern version matches what they wrote in 1935. We shouldn’t attribute to people things they didn’t write.

Before becoming a consultant, I was an employee in a few companies, some of which were admirably successful. In all cases, however, I learned to take their official stories with a grain of salt, as having the truth value of marketing pitches.

Shortly after In Search of Excellence came out in the 1980s, I read it and it felt like the uncritical regurgitation of corporate PR. Unsurprisingly, this book had no prediction value on the future performance of the companies it featured.

Yes, Toyota is a great company but I still take their official story with the same grain of salt.

February 27, 2020 @ 3:54 pm

Hi Michel,

Very nice piece of investigative research and analytical summation.

March 1, 2020 @ 8:24 am

In the 1980s a couple of Americans distilled Masaaki Imai’s thoughts and clarified (for want of a better expression) those into a number of basic concepts and principles for kaizen. I regarded this as ‘hearts and minds’ stuff without which the tools and techniques wouldn’t work.

Imai was a recruitment consultant familiar with many companies Japan, and derived them from observation. I’ve just tried Googles ‘kaizen concepts and principles’ …and there are now boatloads! Even the Kaizen Institute has something different – but one of the original ones was ‘customer orientation’, and if kaizen isn’t a trendy word any more I suppose the marketing has to move with the times…

March 2, 2020 @ 7:39 am

I totally agree on the concept of ” the job of philosopher of manufacturing has yet to be filled “. Having spent over 15 years in preaching Lean Manufacturing and TPS to American Manufacturers, I have realized it is very hard to get a buy in to “Toyota Way” not because it is holistic but because it is very contextual.

March 5, 2020 @ 9:47 am

Very true. When digging into the history of lean for my book I found quite a few discrepancies between the official Toyota history and what probably really happened. Toyota is also downplaying the efforts of non-Toyoda family people, and works on legend building for the Toyoda family. But then I would like to point out that this is not necessarily a Japanese-only phenomena, and probably common throughout the world.