Feb 27 2019

Analysis of Oscar TV Viewership | Mark Graban | LinkedIn

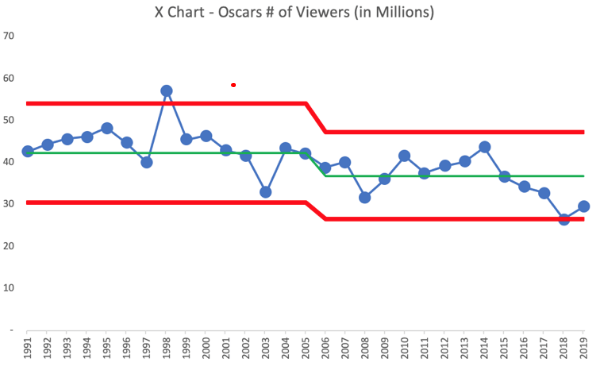

“Initial analysis says Oscars TV viewers and ratings are up over 2018. But, for context, the ratings were DOWN in 2018 compared to 2017.

Instead of reacting to each new data point, look at trends over time using “run charts” or “process behavior charts” (as I created). Did having “no host” make any statistically significant difference in ratings? No. The numbers are just fluctuating. Don’t waste time cooking up an explanation for ‘noise’ in a metric.”

Source: LinkedIn

Michel Baudin‘s comments: What happened between 2004 and 2005? Visually, the downward step is the one feature of the chart that stands out. If the technique Mark used is valid, there should be assignable causes from that period to explain the drop. If you forget the green and red lines and just look at the time series, however, a smooth, long-term downward trend sounds like a better fit. Perhaps Mark should try more modern trend analysis tools besides the venerable XmR chart.

Following a day of spirited discussion, Mark sent me the data and asked for my own analysis, which is in the chart below. The gray band is a 99% confidence interval, calculated without any knowledge of the nature of the numbers. The points outside the band can be assumed to have assignable causes for their unusual high or low ratings, and I took a look at the press reports on a few. As you can see, there is nothing special happening in 2004-2005.

The popularity of a show has nothing to do with a critical dimension on a manufactured part, which is supposed to be constant. The plant organization has the authority to do what it takes to keep it that way. There is no reason why show ratings should be constant.

In addition, while a length measurement qualifies as a raw data point, the published number of viewers of a TV show doesn’t. In the US, it is an estimate based on a poll of 5,000 households. Viewership of the Oscars ceremony in 2019 was 11.5% higher than in 2018. On 5,000 data points, it does not look like a fluctuation. By comparison, political polls use samples of 1,000 to 1,500 voters and claim margins of error of ±3%.

The viewership estimates aren’t just numbers in a table, and you can’t interpret them properly without knowing their backstory.

#SPC, #XmRChart, #ProcessBehaviorChart

February 27, 2019 @ 7:52 pm

Here is the data set. I’d love to see your analysis:

Data

1991 42.7

1992 44.4

1993 45.7

1994 46.3

1995 48.3

1996 44.8

1997 40.1

1998 57.3

1999 45.5

2000 46.5

2001 42.9

2002 41.8

2003 33.0

2004 43.5

2005 42.1

2006 38.9

2007 40.2

2008 31.8

2009 36.1

2010 41.7

2011 37.6

2012 39.3

2013 40.3

2014 43.7

2015 36.6

2016 34.3

2017 32.9

2018 26.5

2019 29.6

March 10, 2019 @ 1:26 pm

Michel,

I asked Mark for the data to perform my own analysis (before realizing it was already posted here…) using a slightly different approach.

Using the summary statistics, I confirmed the fit of a linear regression model is certainly appropriate for the big picture view. However, if we are interested in whether there was a shift in the viewership, the linear model would, for the most part, hide this fact.

Instead of using linear regression, I applied several loess curves – specifying different levels of bandwidth (“span” in R). While a bandwidth of 1.0 replicates the linear trend, a bandwidth that is too low simply overlays each data point. Even with a high bandwidth, there seems to be a definite shift around 2005.

My interpretation of the trend analysis would be that viewership started dropping around 2000, leveled off in 2005, then started dropping again around 2015. I don’t think I can post my results here, but they are available if you would like.

-Ryan