Dec 11 2011

Problem-solving: Dr. House versus the Shop Floor

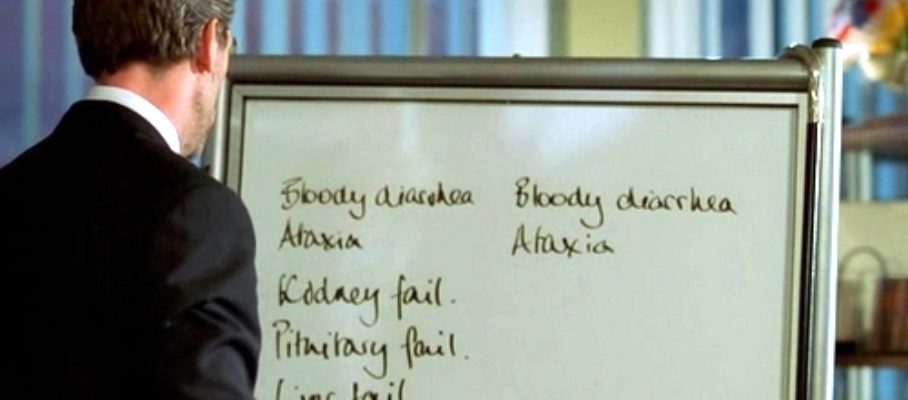

Dr. House‘s fictional team of doctors may be the most famous problem-solving group on the planet. Week after week, they solve daunting medical mysteries under an abrasive, unfeeling leader, working in their differential diagnosis sessions with nothing more than a tiny white board to write lists of symptoms.

In real life, Steve Jobs, a man with character flaws on a par with Dr. House, was able to lead teams in the development of products from the Apple II to the iPad. In light of this, you may wonder why, when faced with problems like an occasionally warped plastic part or wrong gasket, we need to have a team go through brainstorming sessions in which no idea is called stupid, draw fishbone diagrams and formally ask five times why the defect was produced and why it escaped.

House’s team, Apple engineers and Pixar animators are in professions they chose and for which a thick skin is required. They are the product of an education, training and experience in which abuse is used to filter the uncommitted. By contrast, assemblers and machinists are there not to realize childhood dreams but because these are the best jobs they could get. In addition, if they have even a few years of experience in a non-Lean plant, they have been trained to do as they are told. Outside of work, they can be artists, do-it-yourselfers, or community leaders, but they have not been expected to use the corresponding skills at work.

Over the past decades, many manufacturers have realized that this is a mistake, and that there are emergency response situations that are resolved faster with the participation of the people who do the work than without it, and many small improvement opportunities that are never taken unless operators take them on. But welcoming and soliciting their help is not enough. Historically, the first attempt was the suggestion system, dating back to 1880. It is still in use at many companies, including Toyota, but, while it is part of continuous improvement, it is not an approach to problem-solving. Employees make suggestions about whatever they have ideas about; problem-solving, instead, requires a focus on a subject identified by management or by customers, and usually needs a team rather than an individual.

Kaoru Ishikawa’s concept of the Quality Circle in 1962 was a breakthrough, not only in organizing participants in small groups but also in teaching them the 7 tools of QC to solve quality problems, as well as brainstorming, PDCA, and presentation techniques. The key idea was that pulling a group of shop floor people together was not enough. Quality Circles still exist, primarily in Japan, but the ideas of providing technical tools and a structure to organize small-group activities around projects have propagated many other areas. Setup time reduction projects for example, can be run effectively like Quality Circles but with the SMED methodology taught instead of QC tools. Conversely, if working on quality issues, a Kaizen Event team may use the same technical tools as Quality Circles, but is managed differently.

To an uninvolved engineer, a scientist or a medical doctor, “problem-solving” as practiced by shop floor teams may appear crude and simplistic. He or she may, for example, view a fishbone diagram as a poor excuse for a fault-tree because it makes no distinction between “OR,” “XOR” or “AND” combination of causes. In the fishbone diagram, these details are not omitted for lack of sophistication but instead by due consideration of the purpose. You can fill out a useful fishbone diagram in a brainstorming session with a problem-solving team, but you would get bogged down in details if you tried to generate a full-blown fault-tree. There are many simple techniques that could potentially be applied. The value of a problem-solving method is that, for a given range of problems, it has shown itself both sophisticated enough to work and simple enough to be applied by the teams at hand.

In this as in every other aspect of Lean, it makes a difference whether an approach is adopted for internal reasons or to comply with an external mandate. A customer that has developed a problem-solving methodology may require suppliers to adopt it when responding to quality problem reports. The suppliers then formally comply, but it may or may not be effective in their circumstances. For example, a car company that buys chips from a semiconductor manufacturing may mandate failure analysis on all defective chips, but this analysis will provide information on process conditions as they were six months before, when the chip was made. Since then, the process that caused the defect has gone through three engineering changes that make the results irrelevant. These results would have been relevant for mechanical parts with shorter processes and less frequent engineering changes, but the car company doesn’t differentiate between suppliers.

Jan 19 2012

Toyota training center in Karnataka, India

Via Scoop.it – lean manufacturing

There is something strange taking place in Bidadi, near Bangalore. Well-dressed young men in some kind of corporate uniform seem to be walking in single file in a marked side-lane that wends its way around a well-groomed, green campus.

Via www.business-standard.com

Share this:

Like this:

By Michel Baudin • Press clippings 0 • Tags: Lean manufacturing, Toyota, Toyota Production System, TPS, Training