Jan 17 2012

Manufacturing and Wealth

When you are engaged in an activity, it is easy to endow it in your mind with qualities an outsider would not see. Manufacturing produces tangible, physical goods, things that you can see, touch, use, and express your social status with. It is a necessary sector of the world economy and, as manufacturing professionals, we have the privilege of working in it. But we have no grounds to claim that it is the only true way to create wealth.

What is wealth, anyway? To accountants, it is the difference between the totals of what you own and what you owe, synonymous with net worth; it is expressed in money and easily quantified. To others, it is how long you could survive if all your sources of income dried up, and expressed in time, however it might be measured. To others yet, it is related to human relations and happiness.

In none of these meanings does it make sense to assert that the production of material goods is the only source of wealth. This leaves out movie making, health care, tourism, or software development, just to name a few activities that generate wealth for many. As much as I personally like manufacturing, reality is that converting materials into products is only one of many ways of getting other people to pay. Making things is necessary, and somebody needs to do it. But immaterial goods or services are equally valuable creations, that can be exchanged for material goods.

18th century physiocrats thought that agriculture was the only true wealth creation. They were deluded because agriculture was the dominant sector of the economy of their day. Just because manufacturing was dominant for, say, 150 years doesn’t mean that sector has special virtues. In advanced economies, I see it headed in the same direction as agriculture : a vital and important sector, but employing a small, highly skilled fraction of the work force. It has been moving slowly and steadily in this direction since 1960, and I don’t think it can be reversed, no matter what politicians may say.

On the other hand, the human and social consequences can be anticipated. A production operator with 15 years of experience on the same machine is vulnerable; a multi-skilled machinist is much more likely to be retained and to find a rewarding alternative job if necessary. Schools can train young people wishing to make a career in manufacturing to meet the rising requirements.

Like agriculture, manufacturing matters because we need the goods, not because it provides jobs. Whether we make the goods or buy them is a decision that should not be based on direct labor cost alone but instead on all the relevant issues, including engineering, quality, logistics, intellectual property, the skills base, customer communications, public relations, taxes, etc.

Jan 24 2012

Lean versus the Toyota Production System

Is there a difference between Lean and the Toyota Production System (TPS)? This is a recurring question. The short answer is yes, but, when you look deeper, it is an issue of packaging as well as of substance.

If you are working in a car company, you cannot openly say that you are using Toyota‘s production system. How could you borrow such things from a competitor, especially if you have been in the business 50 years longer? It is embarrassing to employees, and a weak marketing message. So, regardless of how much you actually use from TPS, you must call it your own “Production Way” or “Operating System,” or…

A generic name like Lean clearly has many practical advantages over TPS. This being said, the minute Lean branched out from Toyota, divergence was to be expected. Major tools of Lean, like Value-Stream Mapping or Kaizen Events are either minor or non-existent in TPS, while the jidoka column of TPS is largely ignored or misunderstood in Lean. See Art Smalley’s presentation at the 2006 Shingo Prize conference, or Working with Machines. The combination of Lean with Six Sigma is also popular in the US, even though Toyota evaluated and passed on Six Sigma.

The umbilical cord, however, was never broken, and the promoters of Lean still use Toyota as a reference. Clearly, nobody would be interested in Lean if it weren’t backed up by the Toyota story, and this raises the question of how far Lean can drift from TPS and still retain this vital link.

The following two comments in the Leadership and Lean The Top 5% discussion group on LinkedIn, highlight the issues. This is what Allison Corabatir has to say, based on her experience at Magna:

Who would argue with that? Anna Johnson, on the other hand, describes a very different experience:

When Anna says that Lean “emphasizes cost cutting, headcount reduction,” she describes a 180-degrees turn away from TPS. This version of “Lean” isn’t just a watering down but a betrayal. It is taking the approach with which financial managers have hurt US Manufacturing from the 50s to the 70s, and calling it Lean to mislead audiences into believing that it is Toyota’s approach.

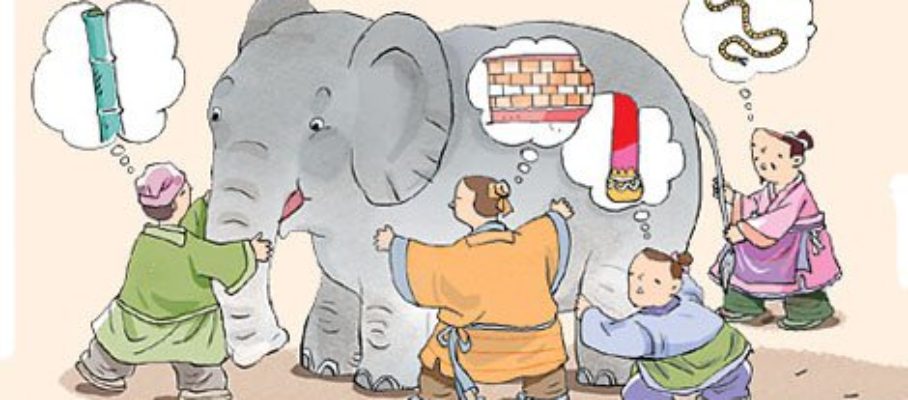

Anybody can slap the Lean label on anything, and it is only a matter of time until this free-for-all makes it worthless. It results in implementations that are best described as L.A.M.E. (Lean As Mistakenly Excecuted) or L.I.N.O (Lean In Name Only). To avoid this, you have to start from the underlying principles of TPS and deploy them in an context-appropriate fashion, but it is easier said than done, because Toyota didn’t do a great job of articulating these principles and we have to reverse-engineer them from TPS.

Lists of principles can be long, abstract, vague and toothless like the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights, or short, specific, and actionable, like the US Bill of Rights. In The Toyota Way, Jeffrey Liker spells out specific and actionable principles, but there are 14 of them, which is too many to remember. The Lean Enterprise Institute has 5 principles, easier to remember but focused exclusively on the flow of materials. They say nothing, for example about human resources. You could claim to follow these principles while practicing yo-yo staffing, hiring massively in boom times and laying off in recessions.

The HBR article on Lean Knowledge Work summarizes Lean principles as follows:

There are good reasons to use the word Lean rather than TPS to designate what we do. Lean evolves in many different directions as it inspires people in different industries to pursue improvement in ways that work in their context, and it is healthy that they should do so. But there will always be bandwagon jumpers just using the label to sell products or services.

Share this:

Like this:

By Michel Baudin • Asenta selection, Management 21 • Tags: Lean, Lean manufacturing, Toyota, Toyota Production System, TPS