Jan 16 2014

What a Coffee Cup Taught Me About Poka Yoke and Human Errors | Peter Abilla

See on Scoop.it – lean manufacturing

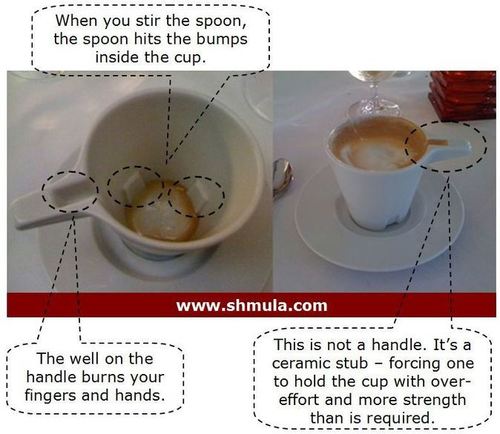

“Human Errors, Poka Yoke are concepts brought to life from my experience with coffee cup. One can learn a lot about Poka Yoke and Human Errors. This is a story about what a coffee cup taught me about how poor design in our products and systems invite human error.

Many years ago, I had to travel to Dublin every few months for work. […] One very early morning while waiting for the taxi to pick me up at my hotel to take us to the airport, my colleague with whom I was traveling with at the time had ordered coffee while I ordered a Coke since I’m not a coffee drinker. They brought him his coffee in this cup.”

With its unsightly bumps and nooks, the “fancy cup” you show is not even pretty, which makes you wonder what the designer had in mind. The issues you bring up, however, are more about usability engineering in Don Norman’s sense, than Poka-Yoke.

A properly designed handle is self-explanatory in that any user who has never seen a cup will immediately understand what it is for. But it doesn’t make the cup mistake-proof: there is nothing physically preventing you from pouring coffee onto it while it is upside down.

Usability engineering is about controls that look and feel distinctive to the touch — as opposed to rows of identical buttons — that give you feedback when you have activated them, that have shapes that naturally lead you to use them properly, that respect cultural constraints in the meaning of shapes and colors, etc.

Applying these principles in designing human interfaces reduces training costs and the risk of errors. It is valuable, but it does not prevent errors.

Incidentally, why do so many cultures, including Japan and China, use cups with no handles? An alternative to handles to avoid burning your fingers is the double-walled cup, and I have seen some from China. Otherwise, I have resorted to the Arab way of holding a handleless tea cup: between my thumb on the bottom and my index finger on the rim.

See on www.shmula.com

January 16, 2014 @ 10:28 am

Comment on LinkedIn:

January 16, 2014 @ 1:27 pm

I had an opportunity in 1989 to discuss Poka-Yoke with Shingo himself. Below are extracts from my notes on his comments, and my own experiences over the last 22 years. Initially he chided me for talking about it as an individual technique, and said it should be seen as the tool for implementing his system of ‘source inspection’ and guaranteeing zero defects.—

Shingo explained that traditional ‘long cycle’ inspection systems wait until an error in action produces a defective item, the defective item is then found by inspecting the output. His concept of source inspection uses the ‘short cycle’ inspection system. In this system the action itself is checked 100% using mechanical means. If an error occurs, immediate action is taken to correct it before a defect is produced. With this methodology we can guarantee zero defects to the final customer.—

The basic system is simple;

The Poka-Yoke methods/devices should be designed to detect deviation from the standard actions and outputs required to satisfy the customer’s requirements.—

This can be done in three ways;

a) Physical contact.

b) Fixed values.

c) Motion steps.

In some cases at the original design stage the part can be made a Poka-Yoke device by ensuring it can only be assembled/used in the correct way.—

They should also check for deviation in the 3M’s of actions and items;

Missing. Action or item not there.

Misplaced Action or item there, but in wrong position.

Malformed. Action or item are there but wrong, size, shape, colour, temp etc.—-

When designing Poka-Yoke devices they must check for specific deviations in the 3M’s using; a, b and c. This can be done with a ‘what could happen’ 3 M’s analysis.—

The Poka-Yoke device should then;

1) Control the operation. Stop the process when an error or defect occurs.

2) Warn the operator. Signal to the operator that an error or defect has occurred.—

They should be applied at the following check points;

1) The source action. (source check) This is the ideal as it gives zero defects.

2) Output of the action. (self check) . This is our second choice as the output will be defective if the PY device is activated, but it will not be passed to the internal customer.

3) Before the next process. (successive check). At this stage the item will be defective if the PY device is activated, but it cannot go to the final customer.—

With this system in place it is now possible to consistently achieve;

‘Zero Defects in our activities and production processes’.

This was Shingo’s original goal in 1965.—

If applied to safety it is possible to achieve ‘Zero Accidents’. I do not understand why this methodology is not more widely used in this area.—

The most impressive example of Shingo’s system I have experienced was on an assembly line for inlet manifolds in Japan. We were allowed to work on the line and challenged to produce a defective assembly. It was impossible to produce one, and we had some very talented people trying.—

Once our front line people understand this system they become some of the best designers of Poka-Yoke devices.—

Poka-yoke should be seen as the device for implementing Shingo’s zero defects system.

The goal is to identify deviation from the desired conditions or actions in any situation.

A good example is the selector stick on an automatic car gearbox. If the stick is not in the park position the poke-yoke switch is not activated and the engine will not start. Zero defects in all situations. Shingoe pointed out to me that this would be impossible to achieve with statistical techniques.

BRILLIANT IDEAS | onlyPics

January 18, 2014 @ 3:08 am

[…] What a Coffee Cup Taught Me About Poka Yoke and Human Errors | Peter Abilla […]