Dec 22 2011

The Lean Body of Knowledge

Efforts at implementing Lean have become pervasive in manufacturing, branching out from the automotive industry to electronics, aerospace, and even food and cosmetics, not to mention efforts to adapt it to construction, health care, or services. As a consequence, the knowledge of Lean, proficiency in its tools, and skills in its implementation are highly marketable in many industries.

There is, however, no consensus on a body of knowledge (BOK) for education in the field, and my review of existing BOKs and university courses confirms it. A consensus is elusive because Lean emerged as the accumulation of point solutions developed at Toyota over time, rather than as the implementation of a coherent strategy.

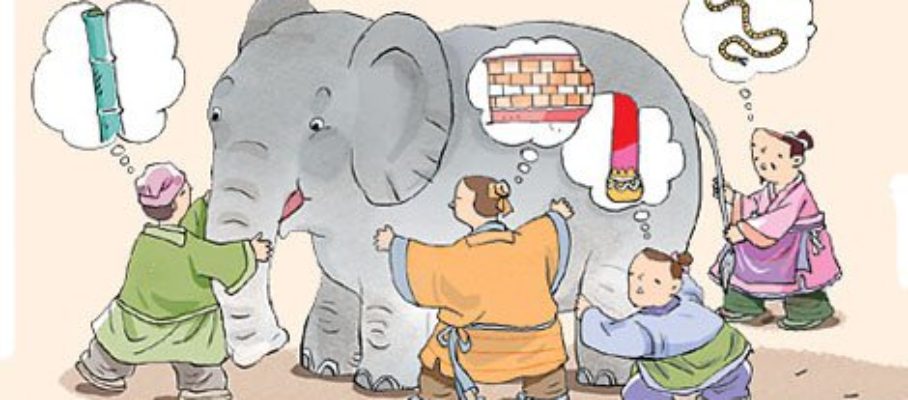

As Takahiro Fujimoto explains, there was no individual thinker whose theories started the company down this path. Decades later, we are left with the task of reverse-engineering underlying principles from actual plant practices. Those who have attempted it produced inconsistent results because they have gone at it like the six blind men with the elephant: their personal backgrounds, mostly in business school education, management, or even psychology allowed them to see different slivers of the Toyota system but not the whole, giving, in particular, short shrift to its engineering dimension.

In the following paragraphs, first I explain what I think the Lean BOK should be. Then I review five programs offered in the US by universities and professional societies and highlight where they differ.

Contents

My view of the Lean BOK

A well-rounded program for manufacturing professionals would provide Lean skills to all the professionals involved in designing and operating manufacturing plants. Organizations that are successful at Lean do not rely on one department to “do Lean” for everybody else. Instead, Lean is part of everybody’s job. There are basics that everybody needs to know, and then there are different subsets of skills that are useful depending on where you work in the plant.

Beyond the common background, the knowledge should be organized around functions performed by people. In this way of thinking, Visual Management, for example, would not be a stand-alone subject, because factories don’t have “visibility managers.” On the other hand, plants have assembly lines, machining or fabrication shops, shipping and receiving departments all in need of visual management. As a consequence, visual management is part of the training of professionals in assembly, machining, fabrication, logistics, quality, maintenance, etc. And each one only needs to know visual management as it is relevant to his or her position.

Over time, Lean should migrate into the mainstream of manufacturing and industrial engineering, and lose its separate identity, both in industrial practice and in engineering and management education. This has been the fate of successful innovations in manufacturing in the past. For example, the “American system of manufacture” to which we owe interchangeable parts is now only a subject for historians. It is not the object of a standard or certification, and nobody explicitly undertakes to implement it. That is because its components — engineering drawings, tolerances, allowances, routings, special-purpose machines, etc. — have all become an integral part of how we make things. Likewise, in Japan, TQC is no longer a topic, as its most useful components have just fused into the manufacturing culture 30 years ago. This is what must happen to Lean in the next 30 years.

Lean proficiency should be built around manufacturing functions, not Lean tools. From foundation to superstructure, we see the following hierarchy — originally defined by Crispin Vincenti-Brown — and structure the body of knowledge accordingly:

- Manufacturing and industrial engineering of production lines is the foundation, covering every aspect of the physical transformation of materials and components into finished goods. This is about the design and operation of a production lines using different technologies and working at different paces.

- Logistics and production control build on top of this foundation, covering both the physical distribution and the information processing required to make materials available to production and deliver finished goods.

- Organization and people covers both what an implementer needs to know in order to lead the Lean transformation of an organization, and to manage it once it is underway. The first part is about Lean project and program management; the second, about the alignment of operator team structures to the production lines, continuous improvement and skills development, and support from production control, quality assurance, maintenance, engineering, and HR.

- Metrics and accountability. This is about appropriate metrics for quality, cost, delivery, safety, and morale. In routine operations, this also means collecting the data needed, computing the metrics, and communicating the results in a way that provides useful feedback. On projects, this means estimating improvements. In both cases, metrics in the language of things need to be translated into the language of money for top management.

A hypothetical participant who would master all of the above would understand both the philosophy and the tools of Lean, their range of applicability, and their implementation methods. He or she would possess the following skills:

- How to read a plant, assess its performance potential, set strategic directions, and start it moving in these directions. This entails the following:

- Characterizing the demand the plant is expected to respond to.

- Mapping its current, ideal and future value streams and processes and detect waste.

- Assessing its technical and human capabilities.

- Setting strategic directions for improvement.

- Identifying appropriate improvement projects for current conditions and skill levels.

- How to generate or evaluate micro-level designs for takt-driven production lines or cells in assembly, fabrication, or machining by focusing on flows of materials and movements of people. The tools include spreadsheet calculations with Yamazumi and work-combination charts, jidoka, board game simulations, full-size mockups, and software simulations as needed.

- How to generate or evaluate macro-level designs for plants and supply chains, involving the organization of:

- Internal and external logistics.

- Milk runs.

- Water spiders.

- Heijunka and Kanbans.

- Lean inventory management.

- …

- How to apply the right tools for quality improvement, addressing:

- Process capability issues with statistical methods/Six Sigma

- Early detection and resolution of problems through one-piece flow and systematic problem-solving.

- Human-error prevention through poka-yoke/mistake-proofing.

- Planned responses to common problems through Change Point Management (CPM), embedded tests and other tools of JKK.

- How to organize people to execute and support takt-driven production, and in particular:

- Set up a systems of small teams, team and group leaders, to carry out daily production as well as continuous improvement activities.

- Set up a Lean daily management system with performance boards and management follow-up routines.

- Generate and maintain a system of posted standard work instructions.

- Apply Training-Within-Industry (TWI).

- Set up and dimension appropriately a support structure for logistics/production control, maintenance, quality assurance, engineering, human resources, supply chain management and customer service.

- How to manage the Lean transformation of a plant from pilot projects to full deployment.

- How to select and deploy relevant metrics to monitor manufacturing performance and estimate the impact of improvement projects both in the language of things and in the language of money.

This BOK is dauntingly large, and new wrinkles are added daily. Fortunately, you don’t need to master all of it in order to be effective.

Review of existing BOKs

I took a look at a few of the existing training programs offered by various institution, for the purpose of identifying the underlying BOKs. Table 1 shows the list. My comments follow.

| University of Kentucky | Lean Systems Certification |

| University of Michigan | Lean Manufacturing Training |

| SME | Lean Certification |

| University of Dayton | Get Lean |

| Auburn University | Lean Certificate Series |

The University of Kentucky program

The University of Kentucky’s program includes Core Courses — a train-the-trainer program — and Specialty Courses — for professionals outside of production operations. Some but not all the specialty courses are targeted at functions within the organization but others are about tools. Just the core courses add up to three one-week training sessions, while each specialty course is typically a one- or two-day workshop.

From the University’s web site, however, I cannot tell when, or if, participants ever learn how to design a machining cell, or an assembly line, or how to reduce setup times. In the core courses, it’s great to talk about mindsets, culture, and transformational leadership, but where is the engineering red meat?

The specialty courses address planning, improvement methods, logistics, supplier development, and other unquestionably important topics, but offer nothing about manufacturing or industrial engineering.

The University of Michigan program

The University of Michigan has a program of two one-week sessions with three-week gaps between sessions. This program does cover cell design, materials handling and factory layout, and even rapid plant assessment, that are certainly relevant engineering topics, but I didn’t see anything about the design of lines that are not cells, autonomation, or the Lean approach to quality. There is a module about integrating Six Sigma with Lean, but there is a lot to Lean Quality that has nothing to do with Six Sigma, such as mistake-proofing.

There is also some coverage of logistics, organization, and accountability, but not as much as in the University of Kentucky program.

The SME

The SME has published a document entitled Lean Certification Body of Knowledge, in which the major headers are:

- Cultural Enablers

- Continuous Process Improvement

- Consistent Lean Enterprise Culture

- Business Results

Organization and People issues are treated in 1. and 3. The first two line items under Cultural Enablers are “Respect for the individual” and “Humility.” I am not sure how you can teach this or test for it, particularly humility. It is followed by techniques that have to do with implementation. The topics in 3. have more to do with management once Lean is started, but it doesn’t say it in so many words.

All Engineering and Logistics is lumped under Continuous Improvement, which is clearly a misnomer because many of the Lean techniques in these areas are radical innovations that have nothing to do with continuous improvement. Inside this section, the choice of topics and their structure is surprising. For example, the only method of data collection considered is the check sheet, and it ranks as high in the hierarchy of topics as poka-yoke or one-piece flow.

As the name suggests, Business Results covers metrics and accountability.

The weight of the different areas varies with the level of certification. At the Bronze level, for example, Continuous Improvement counts for 60%; at the Gold level, only for 15%.

The University of Dayton

I have ties with this institution from having taught courses there for many years, and I am still listed among their Experts. But I am not involved with their GetLean Certification program. It is an 8 to 10-day curriculum with a core of 5 days on the following topics:

- Introduction to the Lean Tools

- How to Develop New Metrics in a Lean Culture

- Human Error Reduction: Root Cause Analysis

- Fundamentals of Negotiation

- Strengthening Your Business Services using LEAN Tools

- Managing Projects in a LEAN or Six Sigma Environment

- Managing an Efficient Supply Chain

The choice of topics may seem odd. For example, you might wonder what Fundamentals of Negotiation is doing in a Lean training program, or why Root Cause Analysis only appears under Human Error Reduction. What about root cause analysis of process capability problems?

Auburn University

Of all the Lean programs reviewed here, Auburn University’s probably has the deepest roots, through the influence of JT Black, whose passion for Lean goes back to the late 1970s.

The list of subjects they cover is as follows:

- Principles of Lean

- Value Stream Mapping

- 5s

- Total Productive Maintenance (TPM)

- Quick Changeover

- Pull / Kanban / Cellular Flow

- Sustaining Continuous Improvement

- Lean Office

- Lean Accounting

- Rapid Improvement Event

- Problem Solving

If anything, this program has too much of the red meat that is lacking in some of the others. It could, without harm, emphasize Logistics and Management a bit more.

Conclusion: no consensus

Even when considering the programs solely on the basis of their published syllabi, it is clear that their graduates will have received vastly different instruction, and that the designers of these programs have no common view of what the Lean Body of Knowledge is.

December 22, 2011 @ 11:45 pm

I think you are right that there is no consensus lean body of knowledge. There might be a core area that most sensible people agree on. And then there might be a bunch of optional pieces included in different ways by different people/organizations.

I don’t think that would be so horrible. The big problem I think is the deep understand of the important core just isn’t there in most cases I don’t think. That is the weakness that really matters, I believe. If you were missing a couple of tools or concepts that isn’t a big deal. If you really don’t practice respect for people, for example, the whole effort is not lean and pretending it is by using lean words and tools is pointless.

December 24, 2011 @ 6:42 am

In the Lean CEO group on LinkedIn, Jamie Flinchbaugh made the following comment:

December 27, 2011 @ 11:24 am

I have to concur with Mr. Baudin and the evolution of our continuous improvement systems, not only lean manufacturing (TPS) and six sigma, but additionally in theory of constraints (TOC) or even possibly TRIZ. We are still experimenting to determine compatibility of each & how well they might compliment one another. Then we can integrate each particular system in our problem solving solutions. So, I believe the professionals should study all of them & utilize the one that fits the situation best.

Regarding the critiques for the programs, SME’s has gotten most the praise for their program and working with the ASQ. So, I see the ASQ implementing their own Lean Certification in the near future, which should provide maybe the best research into the Lean Certification BOK. I believe you should continue your critiques into all of these Lean programs. For instance, you did not offer Villanova’s Lean Six Sigma program. They have developed their Lean Six Sigma BOK in conjunction with the Quality Council of Indiana (QCI), the Dept. Of Navy, and Villanova itself. I totally agree though, that the project work needs to be implemented into industry based on certification.

December 28, 2011 @ 12:21 pm

Michel, I am stuck on your first three paragraphs. I will condense them for the purpose of my comments.

“Efforts at implementing Lean have become pervasive1…As a consequence, the knowledge of Lean, proficiency in its tools, and skills in its implementation are highly marketable in many industries2…There is, however, no consensus on a body of knowledge (BOK) for education in the field…A consensus is elusive because Lean emerged as the accumulation of point solutions developed at Toyota over time, rather than as the implementation of a coherent strategy3. As Takahiro Fujimoto explains, there was no individual thinker whose theories started the company down this path. Decades later, we are left with the task of reverse-engineering4 underlying principles from actual plant practices. Those who have attempted it produced inconsistent results because they have gone at it like the six blind men with the elephant: their personal backgrounds, mostly in business school education, management, or even psychology allowed them to see different slivers of the Toyota system but not the whole, giving, in particular, short shrift to its engineering dimension.”

You words are real quite observant. I have made the condensation of these words one of my criticisms of the Lean/Six Sigma movement. “Lean” is the result of years of practicing TQM or CQI. Lean is often placed upon organizational systems that are far from having a quality “quality system”. One day employees walk in to work, and it is said, “You are now Lean” or “you are now JIT”. Lean and JIT are the result of years of practicing quality as you so aptly state. JIT was learned by a culture of ever learning and Japanese auto executives going into a southern US grocery store called Piggly-Wiggly. Without the ever-learning attitude they would never had learned from a store called Piggly-Wiggly. Perhaps today a company can arrive more quickly at the point where it can be said, they are lean or JIT as the result of continuous practiced TQM, that is, if they have a right understanding, but not many do. I am exceptionally leery of a quick fix when it comes to quality. Most folks in corporate circles that I speak have none or little knowledge of the founders of the quality movement i.e. Taylor, Shewhart, Deming, etc. This goes for engineering, quality and management.

Let comment on the footnotes I have added to your exert:

1) Pervasive is the word. Just attach the word Lean onto a company, and supposedly it means something.

2) Highly marketable and the consultants and contractors are making a fortune. The figure I heard concerning the cost of SS at GE was $1B over ten years which resulted in a ROI of Zero. SS claimed $1B in savings.

3) This sentence is profound. Lean came about by the “implementation of a coherent strategy”, not saying one day we are lean.

4) While I agree with you, to reverse-engineer Toyota’s quality system in all its detail and make the results accurate at this late date with all the biases applied by those who would make the attempt, I do think there is a simple way to reverse-engineer TQM. I have done this by looking at Toyota or any company before quality through each of Dr. Deming’s 14 Points. I clearly see these 14 Points written retrospectively covering his entire career. The 14 Points were first published in 1982 in his book, “Out of Crisis”. Dr. Deming was looking back before, during and after his time in Japan through the accumulation of his ever-learning, experience and trial-and-error and condensed this data into the Red Bead Experiment, 7 Deadly Diseases and 14 Points. His overriding focus was the health, welfare and sustainability of the entity called a business or organization and all who are involved in the endeavor i.e. the customer, the worker, leadership/ownership/management, the community, how ever far we take the system we are operating out to. He did not present 14 laws or requirements, but 14 Points. It is truly ingenious to present 14 actions as 14 Points. It gives the hearer the option of pondering and reasoning concerning what he hears, and the opportunity to act on it at the time he concludes the point makes sense in an order. Anyone of his 14 Points if applied to an organization could have an effect, but he was looking for the most positive effect. The context of his work in Japan was the aftermath of the WW2, and infrastructure that was devastated and a population greatly suffering.

For an example of reverse-engineering I will use Dr. Deming’s Point 1, Create constancy of purpose for the improvement of Product and Service. What would be the characteristics of a Toyota before they fulfilled Point 1? There was no constancy of purpose. There were probably many different purposes at odds with one another and some in direct opposition. Did the top and upper management have a constant purpose back before it practiced Point 1? Probably not! There were probably slogans passed around in an attempt to give a consistent purpose but by the time it got to the worker, it was a confused message. Quality, good quality is the constant, universal aim of a sustainable organization. It first needs to be agreed upon by leadership/management, acted on continuously, communicated consistently and passed on to the workers through word and action. Quality begins to saturate are working being. Eventually the culture is changed from the top down. I could go on, but you are smart guy, you get my point.

Just one other thought in the examination of TQM. I think Toyota was a good example of quality development because the “Japanese miracle” has a great historical significance. It took practiced quality to its highest levels in multiple organizations. It reshaped markets multiple times. Toyota was my benchmark of quality until the recent rash of recalls. I think they got themselves in this predicament by violating Dr Deming’s Point 11: Eliminate Numerical Quotas. They gave themselves the numerical quota to beat GM and be the number one auto manufacturer in the world by numbers of cars manufactured. They took their focus off quality and began to be ruled by a number. The consequence was 16M vehicle recalls and counting. My current benchmark on quality resides with Honda, though I have seen some uncharacteristic number of recalls recently. There is no resting on laurels in the realm of quality. It is continuous quality improvement. A culture change and transformation is needed from business as usual. Past success does not guarantee future success. In fact past success might make a fool of you as you try to convince the world your quality issues are customer perceptions. This has been the mantra among US auto manufacturers for more than a generation (30 years). The result of this false mantra has been to take the entire US auto industry to the precipice of being out of business, buy-outs, mergers, bankruptcy, government ownership, the dissolution of multi-billions of dollars of stock and hundred of thousands of employees put out of work to name a few. I could go on.

December 31, 2011 @ 7:57 am

Comment in the Lean CEO discussion group on LinkedIn:

December 31, 2011 @ 8:00 am

Andreas Sattlberger, in the Lean CEO discussion group on LinkedIn, made the following comment:

January 2, 2012 @ 7:59 pm

Comment in the Schlumberger discussion group on LinkedIn:

January 2, 2012 @ 8:00 pm

Comment in the Schlumberger discussion group on LinkedIn:

January 2, 2012 @ 8:01 pm

I am not sure what you mean about the upstream process.

It is not Takahiro Fujimoto who talks about the engineering dimension being given short shrift, but me. Fujimoto writes about the Toyota Production System, which has a solid engineering foundation.

It is the emerging community of Lean implementers in the US and Europe that is neglecting engineering. And I think the root cause of this is that so few of its members are manufacturing or industrial engineers. You run into more MBAs, psychologists, and even defrocked priests than engineers. And since the few engineers in this group don’t have the best marketing and communication skills, their voices are drowned out.

In your situation, it is up to you to correct this imbalance. If you use consultants to help you implement Lean, make sure your consulting team has engineering skills. You don’t need them to have worked on your exact process for 5 years, and you probably won’t find anybody if you make this a requirement. You need them to know Lean, have an engineering mindset, and be quick studies on the specific issues you are facing.

January 2, 2012 @ 8:02 pm

Saurav

Comment in the Schlumberger discussion group on LinkedIn:

January 13, 2012 @ 5:13 am

That is the precise weblog for anyone who desires to find out about this topic. You notice so much its almost arduous to argue with you (not that I really would need…HaHa). You definitely put a new spin on a topic thats been written about for years. Nice stuff, simply nice!

Learning from a consultant versus getting certified | Michel Baudin's Blog

October 27, 2012 @ 6:03 am

[…] For a review of the Lean body of knowledge and five leading certification programs, see The Lean Body of Knowledge. […]